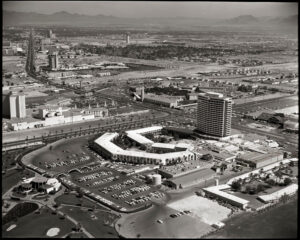

This morning over coffee, I ran across this picture of 1967 Las Vegas:

And, as is the norm for me, one thing led to another, and I fell down the hole. Eventually, I found myself reconnecting with some unpleasant memories.

Fellow crusties might remember the MGM Grand Hotel and Casino fire of 1980, which started in a deli kitchen and ended up gutting the bottom floors and killing 85 people who were stranded on the floors above. The flames incinerated the main floor of the casino and surrounding area, but it was the poisonous smoke — made worse by upper-floor hotel guests smashing out the windows in hopes of breathing fresh air, but instead inviting in all the deadly fumes — that did the worst damage.

While I can’t find the piece of video that has haunted me for 41 years, I remember it like it was yesterday: on a newscast or in a documentary, they showed a person leaping to his/her death in this fire. To this day, I can’t unsee it. Kind of like when they showed someone filming an ultralight aircraft in the sky, and suddenly, the aircraft flipped upside down, and the pilot tumbled out. I was horrified. And this was in the 1980s, mind — not some crazy independent TikTok or YouTube thing. But back to the hotel…

Talk about an absolute disaster waiting to happen. Not only were there no evacuation signs to tell guests where to go in the event of an emergency, there were almost no smoke detectors, and no sprinkler systems anywhere in the massive hotel and casino. Like the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Co. fire in 1911, the tragic death toll in the MGM fire forced city officials to revisit and improve fire safety measures.

Talk about an absolute disaster waiting to happen. Not only were there no evacuation signs to tell guests where to go in the event of an emergency, there were almost no smoke detectors, and no sprinkler systems anywhere in the massive hotel and casino. Like the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Co. fire in 1911, the tragic death toll in the MGM fire forced city officials to revisit and improve fire safety measures.

Anyway, back to the effect this video image had on me. I had trouble sleeping for a while, although, with a newborn baby in the house, sleep was fleeting anyway, so I guess it didn’t much matter. But the whole thing terrified me to the point of insisting for years that any hotel room I booked be on the ground floor.

[Come to think of it, 1980 was a weird year for me all around. Remind me to tell you about the first-person encounter I had in the fall of 1980 with Ed and Lorraine Warren, the demonologists and ghost hunters of the Amityville Horror case. Yikes.]

A short documentary was produced shortly after the MGM tragedy. I don’t remember seeing this, but I’m sure I must have.

Funny how some images stick with you for your whole life. I’m sure we all have those memories. *shudder* Do you have any?